The Victorian era (1837–1901), under the reign of Queen Victoria, is widely associated with rigid social structures, strict moral codes, and deeply entrenched gender roles. Despite these restrictions, beneath the surface of propriety, there existed a vibrant but covert subculture of gender and sexual nonconformity. The LGBTQ+ community of the time faced significant challenges, yet individuals still found ways to explore and express their identities—often through cross-dressing and challenging the period’s rigid gender expectations.

This article explores how cross-dressing in Victorian society became a means for members of what we now understand as the LGBTQ+ community to express their gender and sexual identities, challenge societal norms, and navigate the restrictions placed upon them. From theatrical performances to covert same-sex relationships, the Victorian cross-dressing phenomenon reveals a hidden yet powerful history of gender and sexual defiance.

Gender Norms and Sexuality in Victorian Society

Victorian society was characterized by strict and binary understandings of gender. Men were expected to embody strength, rationality, and leadership, while women were expected to represent purity, modesty, and domesticity. The notion of separate spheres—where men belonged in the public domain and women were confined to the private, domestic realm—shaped nearly every aspect of life.

Sexuality was similarly constrained, with heterosexual marriage seen as the only acceptable form of intimacy. Anything that deviated from this norm was not only frowned upon but often criminalized, especially in the case of same-sex relationships. For LGBTQ+ individuals, these oppressive structures left little room for self-expression, yet some found ways to resist, often through gender disguise and cross-dressing.

Cross-Dressing as a Means of LGBTQ+ Expression

In a society that policed gender and sexuality, cross-dressing became a means for LGBTQ+ individuals to explore their identities in relative safety or to carve out opportunities otherwise unavailable to them. Whether in the world of performance or in everyday life, adopting the clothing of the opposite gender allowed for a subtle challenge to society’s binary expectations and created spaces where LGBTQ+ individuals could live and express themselves more freely.

Ernest Boulton and Frederick Park: Early Gay Icons

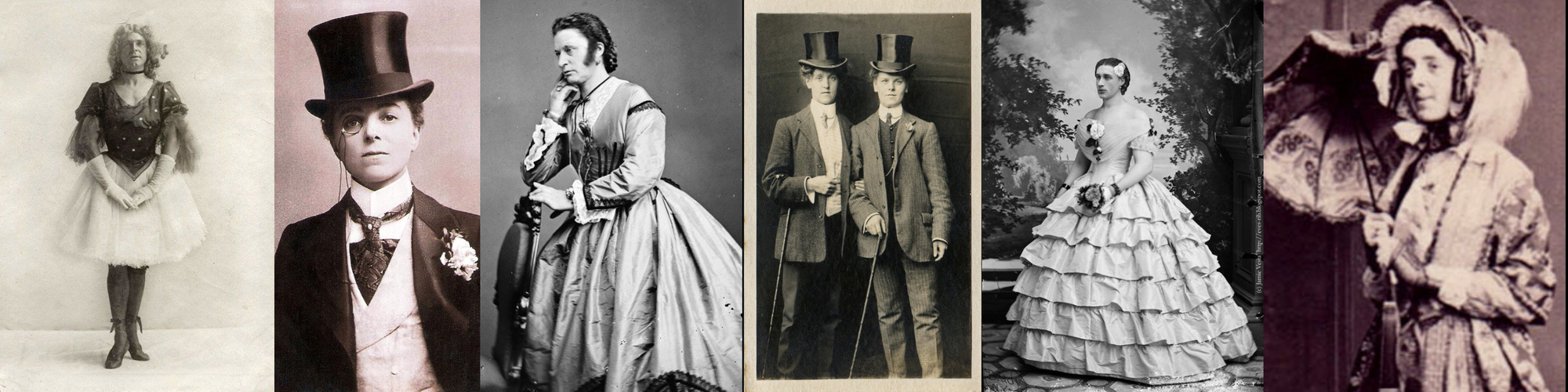

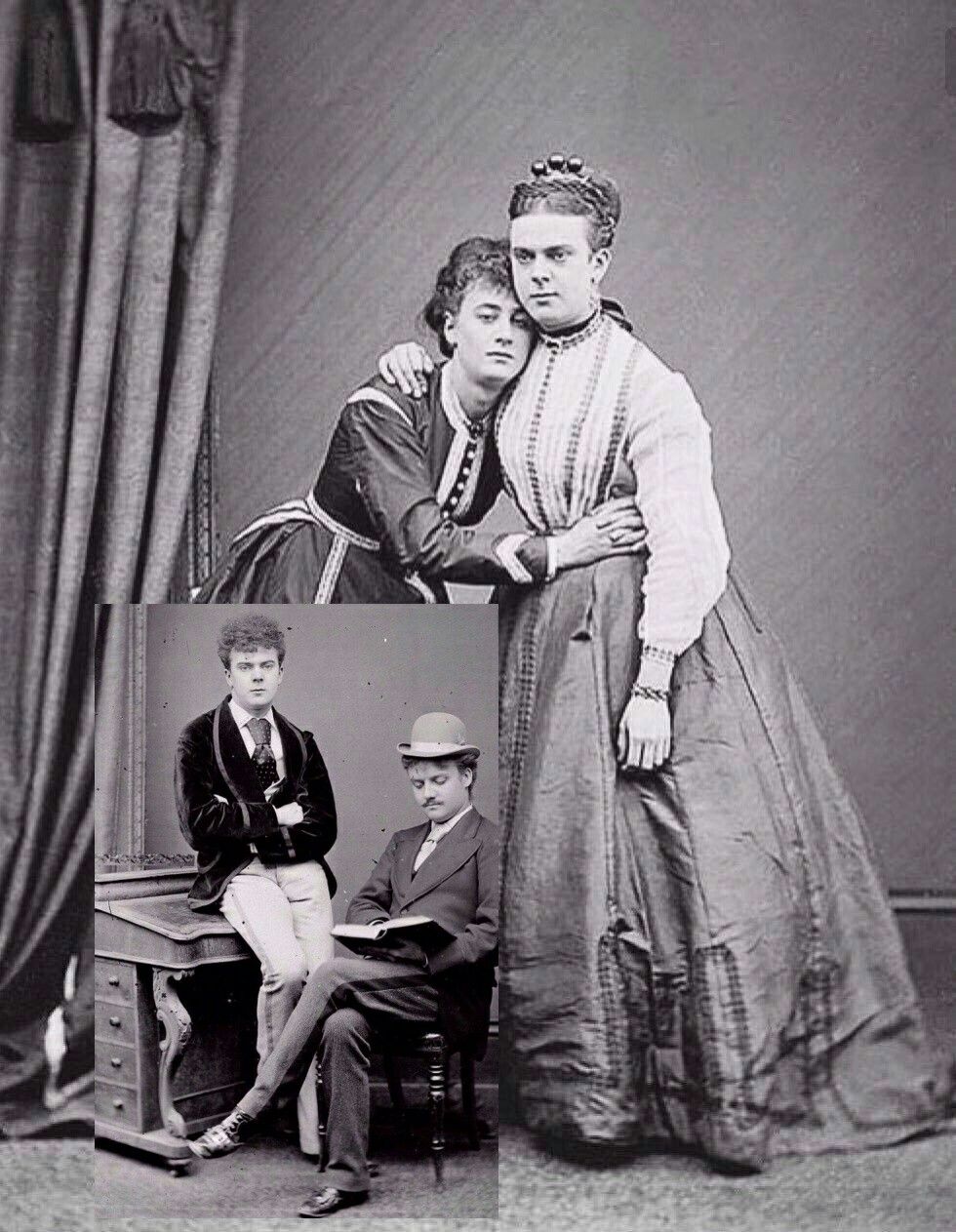

Among the most famous Victorian cross-dressers were Ernest Boulton and Frederick Park, who adopted the female personas "Stella" and "Fanny" in both private and public life. Boulton and Park were actors who frequently performed in women’s clothing, gaining notoriety in London's theatre scene. However, their cross-dressing extended beyond the stage; they dressed as women in their daily lives, moving within London's upper-class circles and attending public events as female companions to male friends.

Boulton and Park were also involved in same-sex relationships, and their cross-dressing allowed them to navigate London’s emerging queer subculture. In 1870, the two men were arrested for "conspiring and inciting persons to commit an unnatural offense"—a charge related to their same-sex relationships, not just their clothing choices. Their trial became a public scandal, but they were ultimately acquitted due to a lack of evidence. Boulton and Park's story highlights how cross-dressing provided a form of protection and expression for gay men in a repressive society, allowing them to explore their sexual identities while avoiding direct persecution.

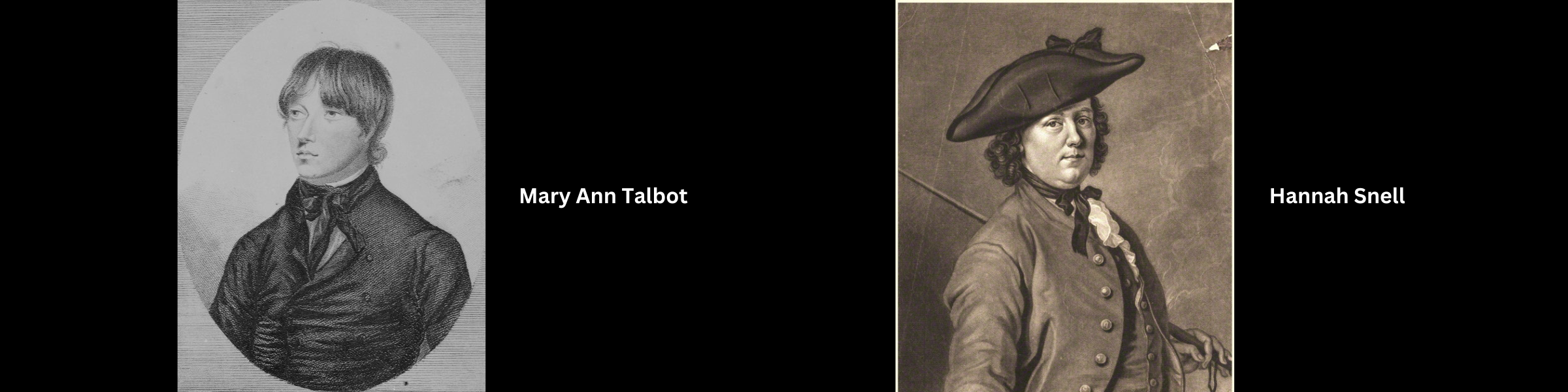

Mary Anne Talbot and Hannah Snell: Gender Identity Beyond the Binary

While many Victorians who cross-dressed did so to subvert gender norms temporarily, others embraced cross-dressing as a way of living a life that aligned with their true gender identity, in what we might now describe as trans or non-binary experiences.

Mary Anne Talbot, for instance, lived much of her life as a man named John Taylor. Talbot dressed as a man to serve in the British Navy and later as a soldier during the French Revolutionary Wars. For Talbot, cross-dressing was not merely a disguise but a way of navigating the world according to the gender with which they most identified. Similarly, Hannah Snell adopted male clothing and the name James Gray to serve as a soldier and later a sailor. Like Talbot, Snell lived for long periods as a man, blurring the lines between gender identity and societal expectation.

These stories suggest that for some Victorian cross-dressers, clothing was not merely a form of disguise but a crucial expression of identity, challenging the rigid gender binaries of the era. While Victorian society lacked the language to describe transgender or non-binary identities, the experiences of Talbot and Snell show that such identities have always existed, even in the most restrictive of times.

The Theatre and LGBTQ+ Identity

Theatre was one of the few places where cross-dressing and gender fluidity could be explored somewhat openly, albeit within the constraints of performance. In the Victorian era, it was not uncommon for male actors to portray female characters, and vice versa, in a tradition dating back to Shakespearean times.

However, for many LGBTQ+ performers, cross-dressing went beyond the theatrical and into the personal. For instance, Vesta Tilley, a celebrated male impersonator, regularly performed in male attire on stage. Her performances were extremely popular, and she became one of the highest-paid performers of her time. Although Tilley identified as a woman, her performances allowed her to explore male roles in a way that was largely accepted by Victorian audiences, even if her private experiences of gender fluidity remain less clear.

For LGBTQ+ individuals, the world of theatre offered a rare space where they could explore gender nonconformity under the guise of performance, all while pushing the boundaries of what was socially acceptable.

Cross-Dressing for Survival and Resistance

While some Victorian cross-dressers were able to explore their identities within the relatively protected world of theatre or upper-class society, others adopted cross-dressing as a means of survival. For LGBTQ+ individuals in the working class, particularly women who sought to escape poverty or violence, dressing as men was sometimes the only way to access jobs, safety, or independence.

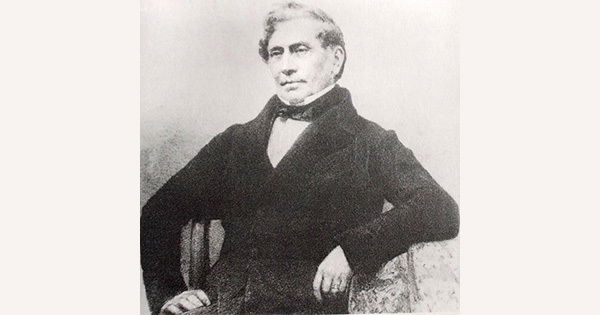

Margaret Ann Bulkley, known to history as Dr. James Barry, provides a notable example of this. Born female, Barry disguised herself as a man to attend medical school and pursue a career in medicine, which was forbidden to women at the time. Barry's life as a man was not simply a disguise to pursue a profession; it became a permanent identity. Barry went on to become a respected surgeon in the British Army, and their true gender was only revealed after their death. While Barry's motivations for adopting a male identity remain debated, their story speaks to the lengths LGBTQ+ individuals would go to in order to navigate a society that denied them access to opportunities based on their gender.

For other individuals, cross-dressing was a means of escaping the harsh realities of life in Victorian society. Some women, particularly those in the lower classes, dressed as men to find work in male-dominated industries, such as the military or manual labour. By doing so, they were able to survive in a society that offered few options for female independence or queer expression.

Legal and Social Consequences of Cross-Dressing

Victorian cross-dressers walked a fine line between public performance and private identity, often facing legal and social consequences for their defiance of gender norms. While there were no specific laws prohibiting cross-dressing, individuals who did so were often charged with public indecency or moral crimes, as in the case of Boulton and Park.

In many cases, the social stigma attached to cross-dressing was just as severe as any legal punishment. Cross-dressers who were caught could face public humiliation, loss of social standing, and even imprisonment. For working-class individuals, the consequences could be even more dire, as they lacked the financial or social resources to protect themselves from persecution.

Despite these risks, many Victorian cross-dressers continued to defy societal norms, carving out spaces where they could express their identities and form communities of support.

Legacy of Victorian Cross-Dressers in LGBTQ+ History

The Victorian cross-dressers left behind a legacy of defiance, resilience, and self-expression that resonates within the LGBTQ+ community today. Their stories reveal that, even in the most repressive of times, individuals found ways to challenge rigid gender norms and explore their sexual and gender identities. Whether through theatrical performance, personal exploration, or survival, these cross-dressers paved the way for future generations of LGBTQ+ individuals to live more openly and authentically.

In many ways, the Victorian cross-dressers were early pioneers of gender fluidity and LGBTQ+ resistance. While the language and understanding of gender and sexuality have evolved significantly since their time, their experiences continue to inspire those who challenge societal norms and seek to live according to their true selves.

As we reflect on the history of the LGBTQ+ community, the Victorian era reminds us that the fight for gender and sexual freedom has deep roots. The cross-dressers of this period, whether motivated by necessity, identity, or art, played a crucial role in the long struggle for LGBTQ+ rights and visibility.

The Victorian era may have been a time of strict gender roles and conservative morality, but it also saw the emergence of a complex and often hidden world of LGBTQ+ identities. Cross-dressing served as a means of navigating this restrictive society, allowing individuals to express their true selves, resist societal expectations, and explore their gender and sexual identities. Whether for survival, performance, or personal expression, the cross-dressers of the Victorian era contributed to the broader history of LGBTQ+ defiance and self-determination.

Their legacy continues to influence contemporary understandings of gender and sexuality, reminding us that the pursuit of authenticity and freedom has always been a central part of LGBTQ+ history.